In the year 2020, just nine U.S. soldiers died in combat. In 2021, it was thirteen, all of them in the Kabul airport bombing during the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. On the final day of that withdrawal, August 30, 2021, the Global War on Terror (GWOT) came to an end, just two weeks before the 20-year mark.

And last year, in 2022, not one U.S. soldier died from enemy combat. The last time we saw that number was 2000 — the year I was born.

The GWOT lasted the vast majority of my lifetime, and today, at the first time in a generation the U.S. isn’t at war, the leading cause of death among U.S. troops is neither combat nor illness nor accident. It’s suicide.

It is a startling reality that more Americans have come to understand: the United States’ 21st century wars were nothing short of devastating to the patriots that volunteered to fight in them.

The Costs of War Project at Brown University puts the U.S. combat toll of the post-9/11 wars at 7,057. But the number of suicides among those who served in the GWOT is over four times that: 30,177. The total number of veterans that took their lives from 2001 to 2020, regardless of service in the GWOT, is nearly 130,000. That figure is greater than the total number of U.S. soldier deaths in every conflict since 1945.

Korea, Vietnam, Lebanon, Kuwait, Afghanistan, Iraq, and all the small conflicts in between — Somalia, Grenada, Beirut. Add them up and you’d still be tens of thousands short of the 21st century veteran suicide toll.

It is as vexing a problem as any — both for our country and for the families.

I should know; on May 29, 2014, my dad Bruce was one of them.

Major Bruce Robert Lafferty, United States Air Force, died on May 29th, 2014. He was 53. Bruce served 26 years in the United States Air Force and Air National Guard as a navigator in the C-130 Hercules. After retiring from service, Bruce worked at the Veterans Administration assisting other veterans to access the resources to which their service entitled them.

He is just one of many. So let me tell you about them.

Phenomena need numbers. Veteran suicide is well quantified, so here’s what we know:

In 2001, the adjusted veteran suicide rate was 23.3 per 100,000. In 2020, it was 31.7 per 100,000, an increase of 36% in the rate.

The suicide rate among veterans has consistently been higher than the civilian rate. In this century, the gap was closest in 2001, when the veteran rate was about 10% higher than the civilian rate. But in 2020, the adjusted veteran suicide rate was 57.3% higher than the adjusted civilian rate. The veteran-civilian gap peaked in 2017, when the veteran suicide rate was 66.2% greater than the civilian rate.

Note that it’s important to adjust suicide rates to account for age and sex – the two largest predictors of suicide in the entire population.

From 2018 to 2020, suicide rates fell across the board in the U.S.. Among veterans, the adjusted rate fell 9.7%. Among civilians, the adjusted rate fell by 5.5%.

In pure numbers, the number of veteran suicides each year since 2001 has fluctuated between 6,000 and 7,000. But in that period the living population of veterans has declined considerably — there are about 25% fewer veterans today, while the national population grew about 25% since 2001 — resulting in a much higher rate.

Veteran suicide statistics based on 2020 numbers:

⅔ are committed with firearms. Poisoning and suffocation are next.

As in the general population, men represent the vast majority of cases.

The suicide rate in 2020 was highest among white veterans: 34.2 per 100,000.

It was lowest among black veterans: 14.2 per 100,000.

The rate is marginally higher among veterans in rural areas – about 10% higher than those in urban areas.

The largest increase was in the youngest group, 18-34

The leading causes of death among veterans are heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries, and respiratory disease. The age-adjusted mortality of heart disease among veterans is nearly ten times higher than suicide.

But among veterans 18-44, suicide is the 2nd-leading cause.

The suicide rate among veterans 18-34 doubled from 2001-2020.

In 2001, about 25% of veteran suicides had recently been in the the Veterans Health Administration. In 2020, it was 40%.

The pandemic had no measurable effect on veteran suicides. A decrease in suicides began in 2019 and continued through 2020 and 2021.

The rate is highest among VHA veterans. The rate among veterans who didn’t see the VHA is lower than the combined veteran rate.

The suicide rate is highest among veterans that left active military service in 2017, 2018, and 2019.

What can be done?

Corporal Clay Hunt, United States Marine Corps, died on March 31st, 2011. He was 28. Hunt is probably the best-known veteran suicide: he is the namesake of major anti-suicide legislation.

Clay Hunt was, in almost every way possible, failed by the system. At one point the VA literally lost his files. The papers went missing!

The VA gave him a 30% PTSD rating - high enough to reflect a real problem but too low for him to be considered a priority. Hunt ended his life shortly after being informed that it would take months for him to see a psychiatrist.

In February 2015, not four years after Hunt’s death, President Barack Obama held a signing ceremony at the White House for the Clay Hunt Suicide Prevention for American Veterans (SAV) Act. It was a landmark law, passed unanimously in both houses of Congress, sponsored by Sen. Richard Blumenthal and the late Sen. John McCain.

Donald Trump’s administration issued the first national strategy in 2018, the National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide. In 2020, the Trump administration went further with a second national strategy: PREVENTS.

And later that year, President Trump signed a second landmark law sponsored by Sens. Jerry Moran and Jon Tester: the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act, which aimed to dramatically expand the size of the VA and DOD psychiatric workforces.

Whether all of these — or any of these — can make an observable difference remains to be seen. I’m not a policy expert. But I have one idea.

Closing Thoughts and an Idea

The first time I walked Arlington National Cemetery — our nation’s most sacred shrine — I felt emotional. Some 400,000 American soldiers, statesmen, and citizens are interred in these hills above the Potomac. Look over the river and you will see memorials to Lincoln, Jefferson, and Washington. Beyond them: the National Mall, where the names of every Vietnam KIA are engraved on a black granite wall.

Walk up the hill past the rows of white headstones and you will see the grave of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Nearby, his brother Robert Francis Kennedy. At the top is Arlington House, the family home of Robert E. Lee, occupied during the Civil War when Lee sided with his beloved Virginia against the Union. The United States selected Arlington as the national cemetery in part to guarantee no further habitation by Lee or his family.

The first soldiers were interred in 1864 amid that war, the United States’ bloodiest conflict – some 620,000 Union and Confederate soldiers died.

There are over 150 memorials and monuments at Arlington. The massive Canadian Cross of Sacrifice honors Americans who volunteered to serve in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1917, before the U.S. went to war. An unassuming plaque memorializes the 1,500 airmen who were interned as belligerents in neutral Switzerland from 1943 to 1945. The Confederate Memorial, placed in 1914, is set to be removed this year on the recommendation of President Biden’s Naming Commission.

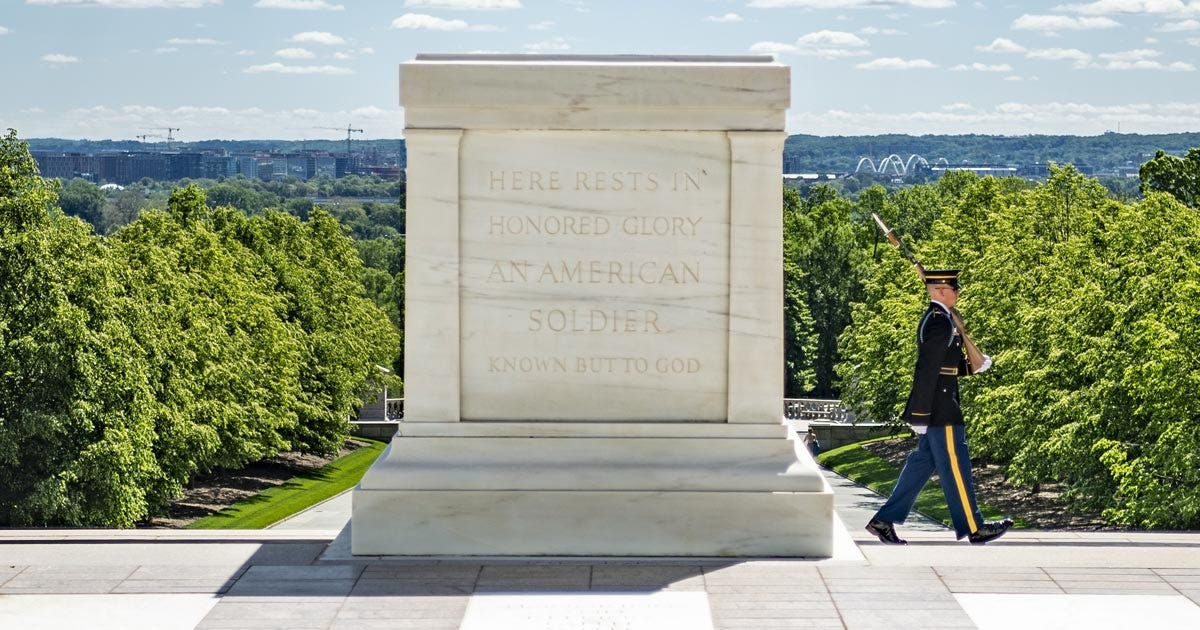

The feeling of profundity (and sometimes contradiction) is all over — impossible to miss. But maybe the most striking, to me at least, are the words engraved on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a singular tomb dedicated in 1921 to all those killed in the First World War whose remains were never identified.

“Here rests in honored glory an American soldier known but to God.”

Known but to God. When I first read those words on the plaque, I thought of my dad. I thought of the incomprehensibility of suicide. I thought of the tens of thousands of military suicides – deaths that often go unspoken because of the inherent shame. They aren’t unknown in the individual sense, like the unknown soldier; but collectively, they are unknown. Forgotten.

And not always by accident. Sometimes, deliberately. As someone who lived it, believe me when I say I understand why we’d rather forget the problem of suicide. But shouldn’t we try to remember? Isn’t that our burden?

New memorials at Arlington require a joint resolution of Congress; no major memorial has been placed since 2006, which was the Battle of the Bulge Monument.

So, my proposal for Congress is simple: adopt a joint resolution instructing the United States Army to create a new memorial at Arlington — dedicated to the remembrance of those soldiers who fell not by enemy hands, but their own. I shall even provide an epitaph for such a memorial:

“To those soldiers who bravely fought our nation’s battles but lost their own.”

I am well aware that a memorial to veterans who died by suicide would be the most contradictory of all. How could we memorialize such a shameful thing? But I think that may miss a key point, which is that memorials aren’t constructed only for the dead. They are constructed equally for the living.

To help us remember; no — make us remember. To help us say “thank you.” To help us apologize. To help us learn.

“To those soldiers who bravely fought our nation’s battles but lost their own.” You have a stunning way with words to share your own loss and draw attention to an important issue. God bless you and your family, Max.

Beautiful piece